Toppling a Delicate World

By Mansi Choksi

Bharati Mirchandani’s face hurt from smiling. She was standing under a spotlight, arms locked with her fiancé’s, at the Bukhara Grill and Restaurant. Waiters in gimmicky Nehru jackets glided across the carpeted room and an invisible voice cracked during the depressing chorus of a ghazal. Bharati leaned towards her man to complain about suffocating under her corset blouse and being tormented by the aroma of chicken biryani while gray-haired guests in Banarasi saris and safari suits lumbered toward them with Sanskrit blessings and envelopes filled with cash.

Feigning distress felt glamorous, especially at her own engagement party. She liked the sound of her name in conversations, the way strangers paid attention to her, how her mother’s eyes shone to match the golden rim of her glasses.

She liked it so much that she forgot it was a farce. She forgot that she was pretending to be the sort of bride her family watched in Indian soap operas. She was in character—face caked with make-up, frame delicate under the weight of cascading gold necklaces, mouth sealed with red lipstick. Her persona even inspired her to pluck off the plastic ring her lesbian partner had given her and cry in front of a mirror. It had to be done to make room for the diamond Kamlesh Lalvani’s family would produce from a small brocade purse.

That both she and the man she was about to marry were gay was no secret to relatives who participated in the spectacle. Yet, they roared with beetle-leaf-stained teeth at jokes like “Marriage is about give and take. Husband gives money and wife takes it. Wife gives tension and husband takes it,” whispered “first night tips” into her ear and offered advice about how to keep a man in control.

Bharati and her fiancé would never have had a marriage greeted with stuffed envelopes had her family not lived in a world fortressed with denial. For this reason, Bharati and other sources in this story have asked that their names be changed.

Bharati’s mother was almost always in the mood to play dumb. When Bharati came out to her at a Hindu temple in Queens, New York, in 2003, it didn’t worry her too much because Bharati’s horoscope clearly said she would marry a man. “She thought it was a phase and it would pass because my horoscope said so,” Bharati says. “She just does not get it.”

Bharati remembers speaking to Meenu Aunty, the matriarch who made decisions about what was to be made for dinner, where the second generation Mirchandanis could buy apartments, which jobs they could take, and whom they could marry. “She told me that whether Kamlesh and I have sex or not is nobody’s business and that I should marry him for the sake of our family,” Bharati says. “I was in my late 20s, we were both under family pressure, and I wanted to help him get a green card.”

While Bharati and Kamlesh lived together, they would send out combined Diwali and Christmas cards and color coordinate clothes for parties. But when the door of their apartment shut behind them, she slept with Tina and he slept with David.

By the time color-coordinated clothes stopped amusing Bharati, she realized she was “a big screw up.” It was 2007, two years after their wedding. She was leading two different lives, but felt at home in neither. “I married Kamlesh because I wanted to cut the umbilical cord. I was out when I did this but all this stuff pushed me back into the closet.”

She needed her family’s acceptance, even if it meant the humiliation of pretending to be someone else, someone who would be intelligible to those who stubbornly refused anything outside of a heterosexual tradition. She also craved to be her own person, marry a woman she loved and start a family.

***

In 1860, British men, likely in tailcoats, cocked hats, and lace cuffs, drafted Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code criminalizing “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” to protect their men from “getting corrupted in colonies with morally lax norms.” Section 377 clubbed homosexuality with bestiality and sodomy, and made these crimes punishable with up to ten years in the clink.

When the British left India in 1947, the law remained as untouched as the crumbling infrastructure. Indians held onto it like a precious memory, even embracing it with the same zeal as when we made English the language of social mobility. We confused homophobia with Indianness, even though our mythology brimmed with references to homosexuality and our religious texts preached the idea of a genderless soul and marriage as a union of two souls.

According to Ruth Vanita, a professor of women’s studies at the University of Montana, homophobia was clearly part of a generalized attack on Indian sexual mores practiced by British missionaries. In an essay titled Same-Sex Weddings, Hindu Traditions and Modern India that was published in the Feminist Review in 2009, she argued that “most Indian nationalists internalized this homophobia and came to view homosexuality as a crime even as they also attacked polygamy, courtesan culture, matriliny and other institutions that were seen as opposed to monogamous heterosexual marriage.” “Prior to this, homosexuality had never been considered unspeakable in Indian texts or religion,” she wrote.

Over the past three decades, Indian newspapers have reported same-sex marriages and double suicides by gay and lesbian people across rural and urban India. Vanita, who is also the co-founder of Manushi, a grassroots feminist magazine in India, wrote that most of these couples were Hindus from low-income groups who did not speak English and were not connected to any movement for gender quality. “Most of them were not aware of the terms ‘gay’ or ‘lesbian,’” she wrote. They framed their desire to marry in terms drawn from traditional ideas of love and marriage, saying, for example, that they could not conceive life without each other, or that they wanted to live and die together.

Marriage has a peculiar place in Indian culture. Hindu philosophy says it’s a metaphor for worldly responsibilities, a mandatory duty of an Indian girl and boy, an occasion that marks the end of childhood. Only those who decide to renounce the world to seek moksha or self-actualization may choose not to marry and have children.

Marriage also became an arrangement between two families, preferably of the same class and caste, to cement these boundaries in a culture that places more emphasis on collective identity than individuality. Just as we don’t choose our parents and siblings, we should not expect to choose our partners or challenge caste structures dictated by birth.

But India is a society in transition. As the economy transforms, a new textured idea of Indian modernity is taking shape. When I turned 18, my family worried about who I was going to marry. “Make sure he’s Gujarati” soon became “Make sure he’s Hindu.” But when I turned 27 and was not getting any younger, the resounding sentiment became “Marry someone before we die.”

At least in India’s big cities, traditional social hierarchies are being challenged, gender equations are being questioned, and arranged marriages are being rethought. Yet for an overwhelming majority of Indians, at home and abroad, marriage is still a collective priority that trumps personal choice.

In July 2009, the New Delhi High Court overturned Section 377, decriminalizing homosexuality after hearing a public-interest litigation demanding legalization of homosexual intercourse between consenting adults. It was the culmination of a gay rights movement that spanned 18 years. But an amendment can’t wipe out a tradition of discrimination. As a result, many gay and lesbian Indians like Bharati, who live in more open-minded societies such as the United States, must still contend with traditional social constructs, gender roles, and marriages of convenience. While they are emancipated by virtue of the location, they are still shackled in the tradition of a country they left behind.

For some, that means cloaking their identities within accepted institutions. Vanita, in her book Love’s Rite: Same-Sex Marriage in India and the West, studied the advertisements in 20 issues of Trikone, a magazine for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender South Asians in San Francisco, California. Eleven and a half percent of all the personal ads that ran from 1998 to 2003 were placed by gay people looking for gay people of the opposite sex to enter into a marriage of convenience.

Another 2 percent were placed by traditionally married bisexual or gay people looking for same sex relationships outside their marriage. One advertiser who was looking for a “straight-acting young lesbian of Indian origin” wrote, “If you, as a gay Indian female, want to be true to yourself without toppling a delicate world, drop me a line.”

***

I met Bharati at Kashmir 9, a Pakistani deli in New York with pistachio couches, greasy tables and an in-house pawnshop. She grumbled in Hindi about how the food was not spicy enough and then settled into a torn seat to show me her discovery: Sahi Rishta (Right Relationship in Hindi), a YouTube channel on which Indian women make pitches to find grooms.

F #8695: Hello I’m a modern day woman, looking for a modern day man. If boy ever opens door for me, I will leave him. I mean he should not think that I cannot open my own doors.

F #4558: I want to make it clear itself now that I have a mini skirt which I wear it occasionally. I want the boy to respect that and his family to allow it. He should not read any adult stuff because it’s a treating a woman an object and we are not an object.

F #4899: Hello, good morning. Myself Ridhima, I’m looking for a suitable groom who will never call me any pet name. Boy should strictly remember that. He don’t call me pumpkin, honey, sugar or any other sweet name because I’m not a dessert…Only interested groom can apply with resumé.

“This one’s mine. I’m sending her my resumé. I want her so bad,” Bharati declares, pointing to F #4899, a pudgy woman with a thick Maharashtrian accent, a woolly fringe, and a patterned Indian shirt with an oval hole around her cleavage.

Bharati is only half joking. She won’t send her resumé to F #4899, but she does hope to find a marriageable Indian girl. The thought crosses her mind every time she meets a girl who can speak Hindi or knows the difference between Katrina Kaif and Kareena Kapoor, both Bollywood actresses. But months of therapy and yoga remind her to conquer these thoughts for now. “I need to work on myself before I get into a relationship,” she says.

It took Bharati and Kamlesh two years to accept that their marriage of convenience couldn’t hold together. Bharati had broken up with her girlfriend Tina—“a Type A investment banker”—and had grown fed up with hiding Kamlesh’s promiscuity from his boyfriend, David. In the summer of 2007, they called off the marriage and Kamlesh moved out of Bharati’s apartment.

It was then that Bharati found Cinthya Garcia on a website that connected lesbians looking for casual sex. They liked each other, had sex again, eventually fell in love and moved in together. “My mother really liked Cinthya and that made me happy,” Bharati says. “But then she would ask us when we were going to settle down. What she really meant to say was, ‘When will you settle down with men?’”

After four years of being together, Bharati cheated on Cinthya with an Indian man. “I was in a messed-up place. Cinthya was not Indian, and it wasn’t working for me,” she says. “It’s important to me, these little cultural things, I want my kids to know Hindi, I want to feel connected to the person. I mean, if we fight, just make me daal and rice, and I’ll forget it. You can’t instill this in someone who doesn’t have it.”

***

When Asif Ali, a gay American of Pakistani origin, came out 21 years ago, he wasn’t looking for a Pakistani man to make a home with. But then, after he had been dating a Jewish American man for three years, he met Ahmed Khan. Now, Asif and Ahmed have lived together for 16 years ago. Their home in Murray Hill has wallpapers with Damask print, handwoven rugs, and the scent of ginger chai. “The fact that he was Pakistani made things easy, it was immediately comfortable. We shared the same pop-culture references, the same values toward our parents,” Asif says.

Asif moved to the US in 1971 when he was three. During the 1980s, when he began to realize he was “different,” the hysteria around the AIDS epidemic was getting intertwined with homophobia. “There were no role models. When I came out myself, I felt very conflicted about my faith, culture, and sexuality, and never understood how I would reconcile these things,” he says.

When he tried to come out to his family, he was reminded that in South Asian households, sexuality was the elephant in the room. Finally, he told his mother in his best Urdu that he was not going to marry. She was expected to figure out the rest.

Although Asif would have Ahmed over and his mother would affectionately feed them kebabs and rice pudding, that didn’t mean she approved of their relationship. “What’s interesting is that we are a homosocial culture. ‘That’s Asif’s friend, they are sleeping in one bed, they are affectionate with each other, that’s the way male friends are.’ And there’s nothing uncomfortable about that,” he says. “On one hand is this real level of comfort, and on the other hand it becomes easy to sweep things under the rug and not acknowledge that two men are actually a couple.”

When Ahmed overtly came out to his mother in 1998, who still lives in Karachi, she proposed placing an ad for a suitable boy. Now when she speaks to Asif on the phone, she calls him her favorite son-in-law. “I don’t have a problem with that because the great thing about being gay is that it makes you open to being of both genders,” he says.

Asif says that his hyphenated ethnic identity as a Pakistani-American allows him to choose and reject aspects of two cultures. For instance, he views marriage in Pakistan as an institution designed to oppress women and is not sympathetic to the spectacle assigned to the same-sex marriage debate in America either. On the other hand, he is fascinated by the queer history of his country: Barbar the Mughal emperor and his gay lovers; Sufi poetry as a form by and for men; Madho Lal Hussain, the composite shrine of a Sufi saint and his Hindu lover.

***

Bharati’s idea of India and sexuality is derived more from memory than mythology. She was born in Chennai, the coastal city in southern India, where Brahmins bathed if so much as the shadow of a lower-caste Dalit fell on them. Her Sindhi mother had eloped with her Telugu father and hoped for a happy life. But a few years into their marriage, he became an alcoholic.

When Bharati was five, and her mother was putting her to sleep, her father burst into the room drunk. He ordered Bharati to sleep on the floor and then had sex with her mother. Bharati lay on the floor, sleepless. “When you’re a child and you see all this stuff… you don’t think much of it,” she says. “But it changes the way you look at sex.”

After ten years of her parents’ marriage, Bharati’s father killed himself in their apartment. Her mother, who already had two daughters, was married off to Murli, a neighbor’s brother who liked to be called Mike. One the second day of her new parents’ honeymoon in New Delhi, Mike was found in his underwear on the streets. “No one told my mother he was bipolar. He suddenly didn’t want to be in this marriage,” she says. “A widow with two children in India is damaged goods, I guess.”

Bharati’s mother begged Mike to take her to Connecticut, saying she could help run his grocery business. He agreed on the condition that her children stay out of his hair. Bharati and her sister moved to the United States in 1989. She was 13 then and she was packed off to Meenu Aunty’s house in Queens, NY where nine people shared one room.

Bharati would often ask her mother to let her come to Connecticut, but her stepfather would only let her stay with them he was in a good mood. His moods were unpredictable, and so Bharati was sent to four different high schools in Queens and Connecticut.

***

All of Bharati’s experiences with sex were nonconsensual until she realized she was gay. She was molested repeatedly by her father’s friend between the ages of five and 12. “I thought that is the only way sex can be,” she says.

At 20, when she was spending a summer in her cousin’s empty dorm room in the University of Minnesota while he interned out of state, her perception of sex changed. Bharati would wake up in cold sweat, haunted by dreams about women pursuing her, of her kissing them. She confided in her only friend, the building maintenance worker, and he introduced her to Melissa: an Irish woman who went only by her first name and whose hair sprung like blonde feather dusters from her scalp. She had tattoos, wrote poetry, and spoke in feministese.

“My sense of identity was communal, it came from my family. And Melissa lived her life the way she wanted to. She was so attractive to me,” she says.

One Friday, when Bharati’s boyfriend missed his flight to Minnesota, she invited Melissa to a Broadway show. “I go to pick her up and the next thing you know I’m in her bedroom and she’s going through stuff to wear, removing her shirt. She was so freaking free, I didn’t know where to look,” Bharati says. “My heart was racing, I had never felt that way with a man. I could feel every cell in my body.”

Melissa introduced Bharati to her girlfriend Kamaya, who hung out with lesbian strippers in Wisconsin. They drove there together. It was the first time Bharati had been to a strip club: women with dollar bills tucked in their underwear propositioned her and argued among themselves to be her “first.”

When her cousin returned to his dorm, Bharati went home to Queens. But she returned liberated from trauma and depression, a state of mind previously such an important part of her identity that she could not recognize herself anymore.

“If I could be two people at once: one for my family and one for myself, I would be the happiest person on this planet,” Bharati says. Her efforts to achieve this—marrying Kamlesh, cheating on Cinythia—pushed her into a corner. She knows this corner well—it’s dark, suffocating and lonely. She’s spent days, sometimes weeks, in bed, avoiding everyone who cares for her. One time, she got so angry with her therapist, she punched the windshield of her car.

Yet, Bharati can’t resist the urge of wanting to please her family or bear to pretend to be “normal” the way her mother wants her to. “If happiness is something that comes from within, I don’t remember what it feels like.”

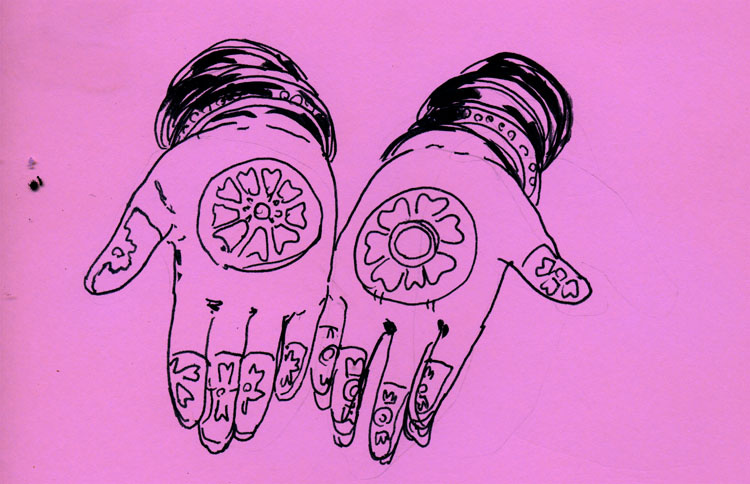

Published in VICE, June 2013. Illustrations by Nick Gazin.